Is the fitbit the solution to our weight problem?

The fitbit dominates the wearable technology conversation offering an accessible tool to improve your health. It has emerged as the leader of the activity trackers market: according to mobihealthnews, fitbit shipped 67% of all activity tracking devices in 2013 and according to Canalys sustained 50% market share in 2014. We see its success in aggregate and in every day encounters: My mom has a fitbit and she loves it and it has worked for her. She often takes walks after dinner to make up for “surplus energy consumption” (i.e. overeating), revealed to her by the fitbit. And she has lost weight after a long-running plateau.

Does it work in general?

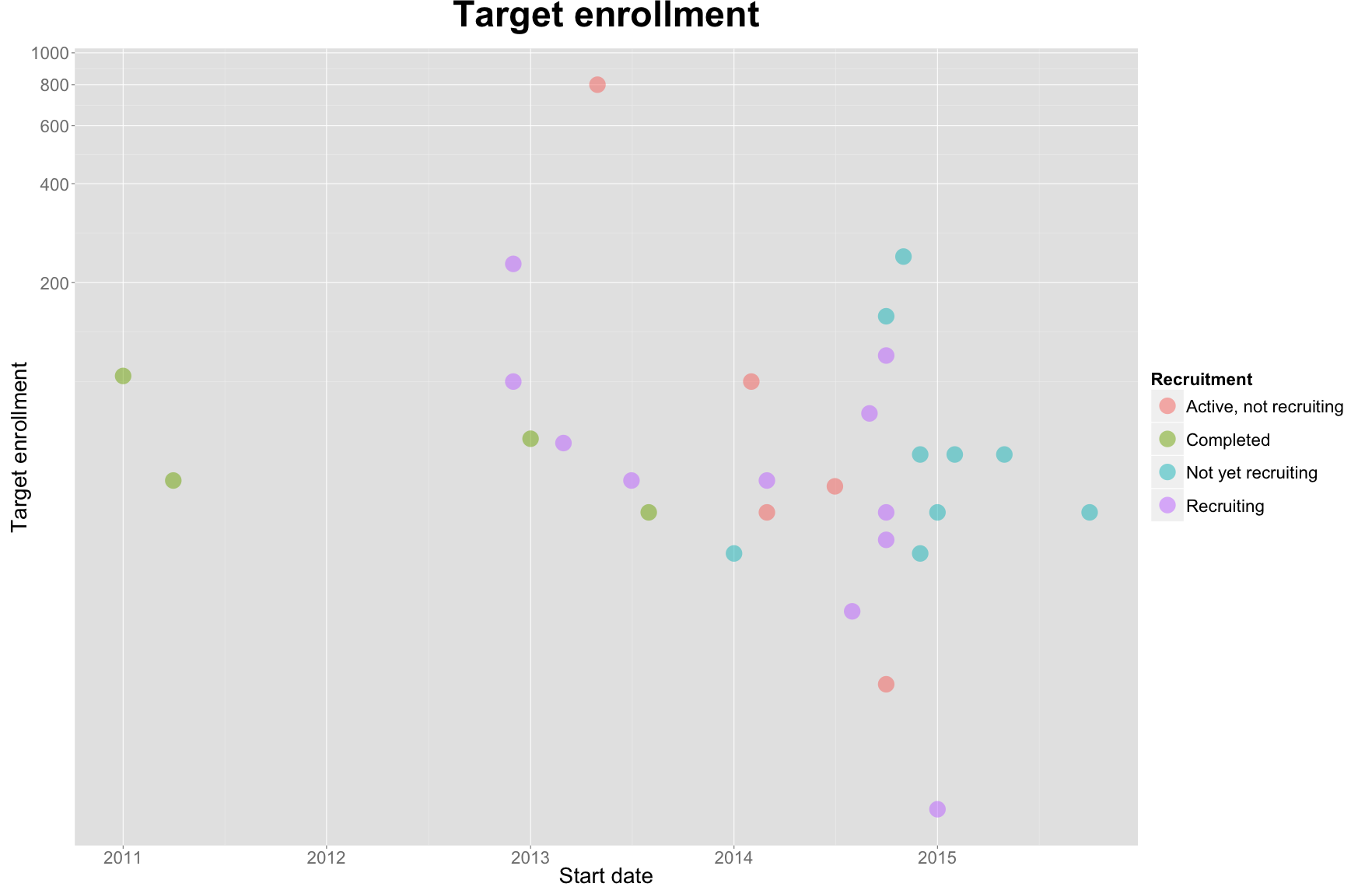

Fitbit claims it does: in an article by entrepreneur.com, fitbit reports its users demonstrate a 43% increase in steps per day and report an average weight loss of 13 pounds when they have weight loss goals. There are, at the time of this writing, 29 studies listed on clinicaltrials.gov for the search term “fitbit”. Of those, only 4 have been completed.

A study of medical residents

Of the 4 completed trials, only one had posted results. Luckily, the single completed study with posted results fascinated me: the study observed the effects of the fitbit on activity levels in hospital residents. Originating from the premise those who medically advise us should themselves be role models of health, the study argues not only does the work of medical professionals itself suffer as a result of unhealthy habits, but it’s also been shown to increase the probabilty of recommending healthy habits to patients. The demanding schedules of residents underlies this problem: the rate of burnout is higher than for other professions.

Out of the 127 residents at Massachusetts General Hospital in, 104 participated in the 12-week trial in two 6-week phases. During the first phase, half of the residents were “blind” as the control arm: they wore a fitbit but were unable to see their activity levels. The other half were “unblinded” as the intervention arm: they wore a fitbit and were able to see their activity levels displayed in real time and on the fitbit web application. During the second phase, all residents were unblinded and participated in a three team competition of most average steps per day.

A number of things surprised me about this trial and its results, some of weaken fitbit’s claims of efficacy:

- Nearly all of the 127 residents participated, suggesting an residents are highly motivated and optimistic about the fitbit itself and / or its outcomes.

- Residents take just under 8,000 steps a day, well above the national average of 5,117 as reported in the entrepreneur article, but still below the 10,000 recommended by the U.S. Surgeon General. Average steps per day was negligibly greater for the intervention group than the control group.

- Compliance fell during the second phase.

- The most promising finding of this trial is the participation rate. Even within a busy hospital setting and with demanding schedules, 85% of residents participated and demonstrated 77% compliance over a 12-week period. It is also impossible to know the effect on average steps per day of just wearing an activity monitor, as all subjects wore an activity tracker and understood their steps were being counted. But, the study agrees that other methods - or perhaps just more residents and thus more relaxed schedules - are needed to make a real difference.

Results on the horizon

More data should flow from the active studies. However, fitbit trials are different from what’s considered a “typical clinical trial”: sponsored by a big pharma company, a typical trial investigates the effect of some intervention with the goal of FDA approval of that intervention. Fitbit has no need for FDA approval so studies are uncharactersitcally heterogeneous.

The characteristics of fitbut studies are:

1. Trial sponsors are involved in only one or two trials and tend to be mostly universities, foundations and healthcare institututes.

Below is a comprehensive list of these sponsors (note, more than one sponsor can be involved in a single trial).

| Sponsor | Number of fitbit studies |

|---|---|

| Aalborg Universitetshospital | 1 |

| Aalborg University | 1 |

| Arizona State University | 1 |

| Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care | 1 |

| Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) | 1 |

| Carol Fabian, MD | 1 |

| Carol Vassiliadis Family | 1 |

| Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario | 1 |

| Danish Heart Foundation | 1 |

| Dr Falk Mueller-Riemenschneider | 1 |

| DSM Nutritional Products, Inc. | 1 |

| EIR (Empowering Industry and Research) | 1 |

| Emory University | 1 |

| Frederikshavn Municipality | 1 |

| GP in the Municipalities of Hjoerring and Frederikshavn | 1 |

| Grand Valley State University | 1 |

| Health Promotion Board, Singapore | 1 |

| Hjoerring Municipaility | 1 |

| International Business Machines (IBM) | 1 |

| JR Albert Foundation | 1 |

| Julie Wang | 1 |

| Katholieke Universiteit Leuven | 1 |

| KMD | 1 |

| M.D. Anderson Cancer Center | 1 |

| Mayo Clinic | 1 |

| McMaster University | 1 |

| Medidata Solutions | 1 |

| Miami Research Associates | 1 |

| National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) | 1 |

| National University, Singapore | 1 |

| New York CFS Association | 1 |

| New York University School of Medicine | 1 |

| Northwestern University | 1 |

| Oakland University | 1 |

| Oscar Film | 1 |

| Phonak AG, Switzerland | 1 |

| Renal Research Institute | 1 |

| Roche Pharma AG | 1 |

| Seattle Children’s Hospital | 1 |

| Simon Fraser University | 1 |

| SOS International | 1 |

| Spectrum Health Hospitals | 1 |

| Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center | 1 |

| Tunstall Healthcare | 1 |

| University of Aarhus | 1 |

| University of California, San Diego | 1 |

| University of Kansas | 1 |

| University of Toronto | 1 |

| Vendsyssel Hospital | 1 |

| Arthritis Research Centre of Canada | 2 |

| Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School | 2 |

| Massachusetts General Hospital | 2 |

| University of California, San Francisco | 2 |

| Vancouver General Hospital | 2 |

| University of British Columbia | 3 |

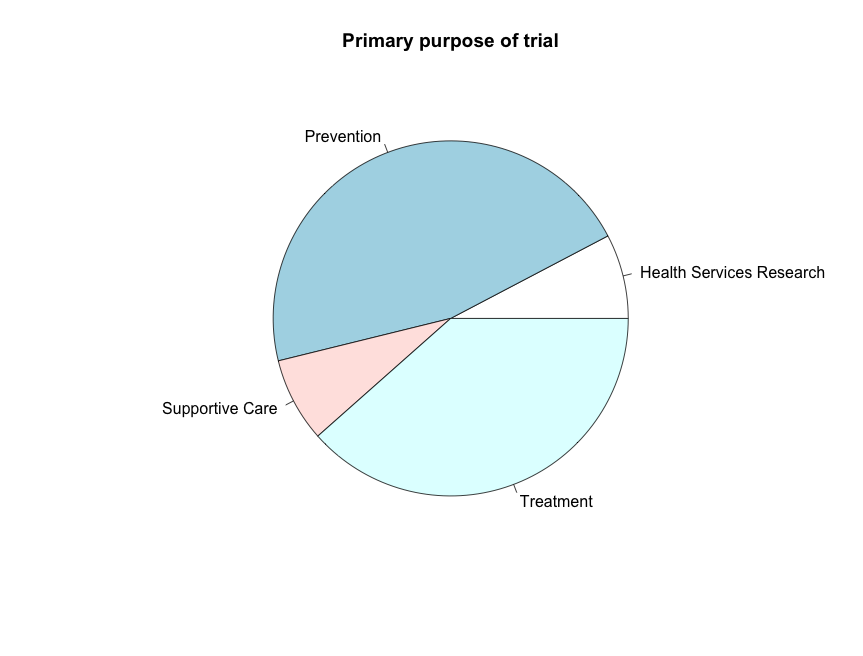

2. Half of trials are focused on prevention, while the other half are mostly focused on treatment.

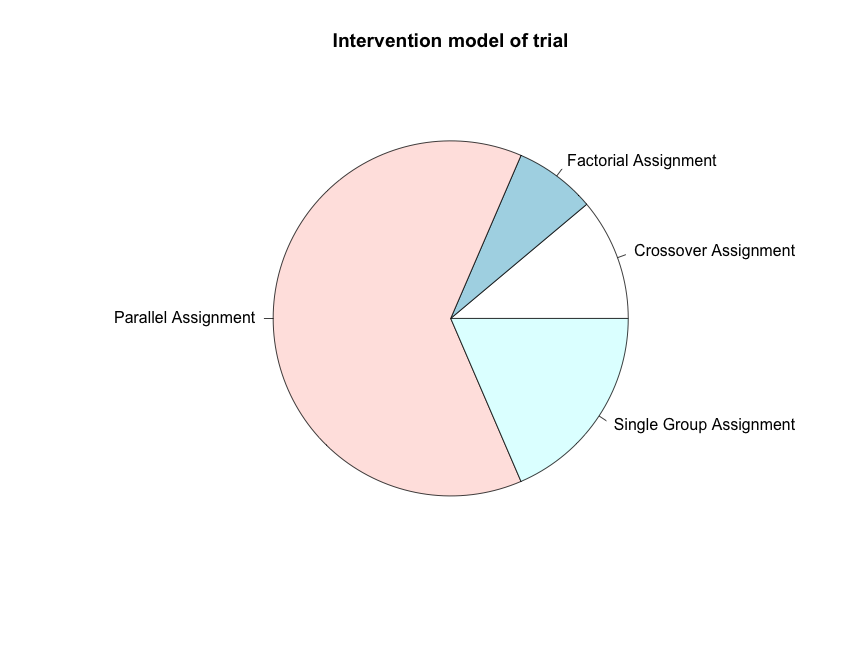

3. Most trials are using parallel assignment, meaning more than one arm of treatment is being administered.

As stated, there is insufficient data to state the fitbit’s effectiveness on health outcomes. But stay tuned, there is more data coming! I posit the activity trackers are making a significant difference on the lives of their consumers, based on personal experience, the enthusiasm of consumers and the growth of the market.